[Excerpt Chapter One]

“There's something wrong with that boy. He frowns for no good reason.” – William S. Burroughs, following a meeting with Kurt Cobain in 1993

El Hombre Invisible

By the dawn of the 1980s, decades abroad and several years holding court among the New York City underground had brought William S. Burroughs to a place of exhaustion, and, once again, addiction. He no longer felt the wanderlust that once propelled him through South America, North Africa, and Europe and informed books like Naked Lunch, The Soft Machine, and The Wild Boys. Now in his sixties, it was time for Burroughs to get clean and go home. But where was that, exactly? Surely not St. Louis, where he was born and experienced a childhood of privilege as the favored son of a Midwestern family of diminishing industrial wealth. By now his parents were deceased, along with his own son, William S. Burroughs Jr., who died in 1981 from cirrhosis of the liver at the age of 33. Burroughs’ steadfast literary secretary, business manager, and friend James Grauerholz would be his closest family in his final years. Concerned for Burroughs’ health, Grauerholz encouraged the author to move to his own hometown of Lawrence, Kansas. Burroughs had been to most places worth visiting and plenty that weren’t, and Lawrence seemed nice, if quiet. And that was good. Lawrence was the kind of town where the jackboots wouldn’t storm in if he wanted to shoot guns at, say, a can of spray paint placed before a piece of plywood. This was the formula behind “shotgun painting,” a creative habit Burroughs took up in his later years that also helped pay the bills—he did remarkably well in the fine arts market. Another interest was animals, specifically those of the feline variety. When asked what was attractive about the sleepy college town, Burroughs quipped that Lawrence provided the opportunity to “go shooting and keep cats.”[1]

The 67 year-old Burroughs was freshly signed to a seven-book deal with Viking Press when he arrived in Lawrence in December, 1981. In the preceding years, he’d given numerous public readings of his work around the world, cementing his reputation among a new generation of artists within the rock, punk, and new wave scenes. But at home in his modest red bungalow, he was just William. “Burroughs was very comfortable because the rest of the town just let him be,” said Phillip Heying, a local photographer who befriended the aging author and who would serve among a small but dedicated crew of locals who took turns making Burroughs dinner and assisting with chores and errands.[2]

Many years earlier, while living in abroad, Burroughs earned the nickname El Hombre Invisible from locals who noted his skill at not being noticed—no small feat for a stiff-limbed white guy on the streets of Tangier. Burroughs by then had plenty of practice dodging authorities, which may be why he believed invisibility was a technique one could learn. The magician revealed his secrets—well, this one at least—in the The Adding Machine, a collection of essays first published in 1985. “The original version of this exercise was taught me by an old Mafia Don in Columbus, Ohio: seeing everyone in the street before he sees you,” Burroughs wrote. “I have even managed to get past a whole block of guides and shoeshine boys in Tangier this way, thus earning my Moroccan moniker.”[3]

In 1950s North Africa, Burroughs chased drugs, sex, and literary immortality to the sound of reed pipes and drums played by musical mystics. His best-known work, Naked Lunch, was largely written in in this heady environment. It would be published in Paris in 1959, while Burroughs was staying at the infamous Beat Hotel in the city’s Latin Quarter. He haunted London in the 1960s, rubbing elbows with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and singing the praises of the “aphomorphine cure” that helped him kick heroin, however briefly. The next stop was New York’s Bowery neighborhood, where he commandeered a converted YMCA locker room affectionately known as “the Bunker” in the mid-to-late 1970s. They were productive years, but Burroughs’ underground celebrity had gone from an entertaining distraction to a sycophantic drag. As Blondie co-founder Chris Stein says, “I think he got to a point at the Bunker where every time he left the house some guy was coming up to him with a manuscript.”[4]

Even if he didn’t leave the house, odds were he’d end up having dinner with the likes of Mick Jagger, Lou Reed, or Joe Strummer, to name a few of the well-known guests who visited Burroughs at the Bunker. But that didn’t pay the soon-to-be-raised rent, which his latest junk habit was already eating into. Given these realities, relocating to Lawrence seemed like the smart choice. Burroughs’ ties to New York remained strong, however, and he would return in later years for social occasions, commendations, and the occasional gig. One major event was his 70th birthday party in 1984, held at a nightclub called Limelight—a former church that now welcomed a congregation of notables looking to rub elbows with the iconic author. Madonna and Lou Reed were there, as well as Philip Glass, Jim Carroll, Lydia Lunch, and rising star Sting, accompanied by then-bandmate Andy Summers. When Burroughs heard that “the police” were at the party, he became concerned, telling a friend, “I don’t know if you’re holding but someone told me those two guys over there are cops.”[5] The fête was fun and the company interesting, but in New York everyone always wanted something.

This was refreshingly not the case in Lawrence. It wasn’t long before Burroughs had established a routine that included writing, target shooting, methadone schedules, and feline feedings. Months stretched into years under the canopy of elm and honey locust trees that decked the city’s wide sidewalks and Gothic Revival architecture. Townsfolk did not view Burroughs as a druggy firebrand, but rather a congenial, if eccentric, old man, which is just what he had become. Lawrence poet Jim McCrary, who befriended Burroughs in his final years, recalled an obliging figure with proper Midwestern manners. “He was a nice guy. You know like, if you came to his house, and you hung around and you left, he would always walk out on the porch and wait until you got into your car. If he drove you home, he would wait until you got into your door.”[6] After years of globetrotting, Burroughs had finally become settled.

Although his social obligations were fewer than in New York, Burroughs maintained a well-populated calendar, with visits from old friends and colleagues, including Allen Ginsberg, Keith Haring, Norman Mailer, Timothy Leary, and Hunter S. Thompson. Admirers from the music world, such as Nirvana's Kurt Cobain, Michael Stipe of R.E.M., Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth, and Al Jourgensen of Ministry also paid their respects. Blondie’s Chris Stein, who spent several weeks in Lawrence in the mid-1980s while recuperating from an illness, first met the old man in 1970s New York. The two remained friends until Burroughs’ death in 1997. “I always thought he was a really sweet guy,” Stein says. “Just a very nice person. I like guns, ya know, so we had that in common.”[7] In the early evenings, Burroughs would go shooting in a nearby cornfield with friends. Later, Stein would head out to a local punk club The Outhouse, on his own. “It was so outlaw and fringe because the club was only accessible at the end of a dirt road and it was literally a cement bunker,” Stein recalls. “I don’t know if they stole the electricity but it was coming off this lamp post or something like that and all these punk bands would come through there and play.”[8] Those bands included the likes of Bad Brains, Circle Jerks, Meat Puppets, and a soon-to-be-massive trio from Seattle called Nirvana. That band’s leader, Kurt Cobain, was a Burroughs obsessive of whom the older writer was genuinely fond.

Teen Spirit and Other Viruses

It is hard to overstate the impact Nirvana’s 1991 breakthrough, Nevermind, had on popular music as well as the lives of the young men who wrote and recorded it. Cobain, bassist Krist Novoselic, and drummer Dave Grohl blew the opening bugle for alternative rock while defining its Seattle-centric sub-genre, grunge. Landing in a music landscape dominated by hair bands and cookie-cutter dance-pop, Nevermind was one of those rare impact objects that are directly responsible for the extinction of an entire species—in this case, hairsprayed and spandexed strutters like Poison, who pranced and pouted their way into the mainstream in the 1980s. Nevermind was responsible for a massive restructuring of the music business, which had previously bet big on glam metal. Now, label execs parachuted into local scenes ready to sign anyone with a goatee and a pawn shop guitar. “Everyone was a little shocked,” said Janet Billig Rich, who once managed 1990s alternative music megastars like Nirvana, Smashing Pumpkins, and Hole. “Everything got really easy because it was this economy — Nirvana became an economy.”[9]

Nirvana’s popularity was epidemic. Nevermind achieved diamond sales status and knocked Michael Jackson from his position at the top of the charts. The band’s videos aired incessantly on MTV, and their backstage brouhaha with Guns N’ Roses at the 1992 Video Music Awards became the stuff of legend.[10] It had been a while since anyone had this kind of culture changing impact, but it had happened before. Elvis Presley’s pelvic thrusts during his 1956 performance on “The Ed Sullivan Show” brought a new carnality to popular music. The Beatles’ 1964 appearance on the same program cemented rock ‘n’ roll as the international language of youth. Since then, music—perhaps more than any other popular media—has matured into a massive, global business.

Commoditized as it may be, no one would argue against music’s power to move the masses, even in today’s so-called distraction economy. In 2014, hip-hop producer Pharrell inspired millions in every corner of the world to make fan videos for his song “Happy.” The track exploded on YouTube, a site whose global reach and influence has come to define “viral.” These days, record labels, movie studios, artists, and political candidates all seek to capitalize on contagion. This is the modern media hustle, where you’re either a pusher or a mark. Burroughs died nearly a decade before YouTube was a glimmer in its developers’ eyes, but he was a lifelong student of influence; specifically how the virus of word and sound can shape the destiny of humankind. As he explained in 1986:

My general theory since 1971 has been that the Word is literally a virus, and that it has not been recognized as such because it has achieved a state of relatively stable symbiosis with its human host; that is to say, the Word Virus (the Other Half) has established itself so firmly as an accepted part of the human organism that it can now sneer at gangster viruses like smallpox and turn them in to the Pasteur Institute. But the Word clearly bears the single identifying feature of virus: it is an organism with no internal function other than to replicate itself. [11]

In the Burroughs worldview, language is a mechanism of what the author called Control with a capital C—an insidious force that limits human freedom and potential. Words produce mental triggers that we can sometimes intuit but never entirely comprehend, making us highly susceptible to influence. But there’s an upside: language can also be used to liberate by short-circuiting pre-programmed ideas and associations. Burroughs believed humanity is held back by constraints imposed by hostile external forces that express themselves in our reality as various aspects of the establishment. Using fragments of word, sound, and image, reordered and weaponized, Burroughs sought to dismantle Control and its systems. His stance inspired other artists across generations and genres to use similar methods to rattle the status quo in ways that even he could not anticipate. You’ll get to know them, and their connections to Burroughs, as our story unfolds.

Burroughs saw reality as hostile, malleable, and possessed of hidden potential that could be actualized through a kind of occult media arts. Though primarily known as the author of such groundbreaking novels as Junkie (1953), Naked Lunch (1959), The Soft Machine (1961), and The Wild Boys (1971), Burroughs was also enthusiastic about audiotape, which he believed could be used to gum up the space-time continuum by playing back pre-recorded sounds in random juxtaposition. Burroughs’ tape experiments have been compiled on such albums as Call Me Burroughs (1965), Nothing Here Now But the Recordings (1981) and Break Through in Grey Room (1986)—all of which have made an impact on the musicians in this book.

In his writing, recordings, films, and paintings, Burroughs sought to subvert habitual thought processes and logic structures. He has few peers in literature, though James Joyce or Thomas Pynchon are similar in that their own authorial feats are both dissociative and evocative. Still, neither of them are as far out as Burroughs, which probably comes down to the purpose behind his writing. Burroughs was convinced that humankind is at the threshold of an evolutionary breakthrough that will allow the species to travel space and time unhindered. In his view, this next and final stage of human development requires a mutation that will only become possible when we overcome the tyranny of Word—that is, language itself, which Burroughs asserted was deeply encoded into our individual biological units. These are the “soft machines” upon which Control’s script is emblazoned; Burroughs’ work was an attempt to circumvent the invisible authority that conditions human experience.

It sounds pretty crazy, but he didn’t come up with it entirely on his own. Burroughs’ “language as virus” premise owes something to metaphysical syllogist Alfred Korzybski, whose theory of General Semantics argues that humans’ central nervous systems have been evolutionarily shaped by language to the extent that it defines our perceptual reality.[12] The only way forward is to expand our scope of comprehension—to stop confusing the map (words) with the territory (perception). Burroughs’ philosophy also has commonalities with William Blake—the English poet, printmaker, and mystic whose proto-psychedelic visions concerned warring gods of liberation and subordination.[13] In Blake’s cosmology, the authoritarian deity Urizen compels conformity through the Book of Brass, the source code of mass influence. This is similar to Burroughs’ own conceptions of Control—that insidious force which limits human freedom and potential through various manipulations, including mass media. The goal of any serious artist, in his view, is to break down the mechanisms of Control by hacking into and disrupting its core programs using the selfsame tools: words, sounds, and images.

Burroughs saw Control as the byproduct of a space-borne mutation that colonized human larynxes millennia ago, and continues to perpetuate itself through language, infecting individuals for no purpose other than viral replication. In which case, Pharrell's “Happy” might have been engineered by Control to produce spasmodic gyrations like the purple-assed baboons frequently referred to in Burroughs’ work. (Exhibit A: “Roosevelt After Inauguration,” a scathing satire of American politics in which the entire Supreme Court is taken over by debased simians.)[14] To Burroughs, all forms of Control are to be rejected. “Authority figures are seen for what they are: dead empty masks manipulated by computers,” he croaks on Seven Souls, a 1989 release by the band Material. “And what is behind the computers? Remote control, of course. Look at the prison you are in—we are all in—this is a penal colony that is now a death camp.”[15]

Radio-Friendly Unit Shifter

For Kurt Cobain, the music business was a particularly grueling prison. Artists with hits as big as “Smells Like Teen Spirit” are expected to criss-cross continents on tours that can last upwards of two, even three years. It’s an exhausting lifestyle to say the least, especially if you’ve got a raging heroin addiction and need to score in order to not feel horribly ill. Even without a junk habit, success—or any form of notoriety, really—can be stressful. Cobain adored Burroughs’ breakthrough work, Naked Lunch, though he may have been unaware of the onslaught its author endured for having written it—including a high-stakes obscenity trial and public misunderstanding regarding its portrayal of addiction. If Cobain did know the story behind the book’s publication, it no doubt deepened the connection he felt. He could also tell that Burroughs wasn’t entirely comfortable in his own skin. Such a condition screamed for self-medication, and for both men that was opiates. It’s possible that Burroughs made junk seem cool enough for Cobain to try; then again, he could easily gotten strung out on his own. In the Pacific Northwest of Cobain’s era, heroin was more prevalent than sunshine.

Before junk, Cobain had music. At times it felt like it was all he had. Music helped Cobain deal with his his parents’ traumatic divorce at age nine; it also helped him through miserable days at school, lessening somewhat his deep feelings of isolation. If music had the power to do that, maybe it could save him from working in a gas station, or worse, in the woods. So, Cobain improbably decided to be a rock star. For his 14th birthday, his uncle gifted him a used electric guitar, which he used to “write his way out,” to borrow a Burroughs phrase.[16] Burroughs himself imagined growing up to be an author who lived in exotic locations and indulged strange vices. He claimed that the purpose for writing is “to make it happen,” and for him, it did. Likewise, Cobain poured his angst and animosities into song, transforming himself from bullied malcontent to the hero of bullied malcontents the world over. And yet it was a case of be careful what you wish for—you might just get it.

Cobain’s rock ‘n’ roll dreams came true, but the reality was more like a waking nightmare. The more people went nuts for Nirvana, the more claustrophobic he felt. His addiction deepened along with his sense of estrangement. Cobain attempted to justify his habit among colleagues and in the media, claiming that he self-medicated to ameliorate an undiagnosed stomach ailment. His pain may have been real, as was the relief that junk temporarily provided. But he was soon profoundly addicted, which only exacerbated his suffering.

Cobain’s personal turmoil was authentically channeled on Nevermind, which served as the soundtrack to a flannel-draped movement that briefly defined 1990s music culture. It only took one shot—the bipolar rave-up “Smells Like Teen Spirit”—and the kids were hooked. Cobain’s status as a depressive martyr has since been maintained by successive waves of young people who ape his look and attitude. At this point, his legend is far taller than the amount of music he left behind; Nirvana t-shirts are worn by everyone from the kid bagging your groceries to Justin Bieber. Trends come and go, but Nirvana still scans as hip and subversive, for the most part due to Cobain’s uncompromising attitude. People continue to be drawn to Burroughs along the same lines. Often, the attraction is superficial—the author’s icon is as at least as compelling as his output (not that the two can be meaningfully separated). A select few, like Cobain, become completely hooked.

Nirvana flipped the music industry on its ear, but there were other pacesetting acts in the late 1980s and ’90s who primed the pump for the alternative revolution. R.E.M., from Athens, Georgia, and Ministry, from Chicago, both rejected the dominant sounds of the day and were rewarded with varying amounts of mainstream success. In 1991, the year that Nevermind was released, R.E.M. issued their second major label album, Out Of Time. Propelled by the hit song and video “Losing My Religion,” the album topped the sales charts in both the United States and the United Kingdom. Singer Michael Stipe also made a trek to Lawrence to visit Burroughs, and the band collaborated with him on a cover of their song “Star Me Kitten” in 1996, one year before the author’s death. Ministry frontman Al Jourgensen became friends with Burroughs in his later years, and even convinced him to appear in the video for Ministry’s 1992 punishing industrial metal track “Just One Fix.” Other artists, like Sonic Youth and U2, also made direct connections with Burroughs in the final decade of his life—their stories will be told in subsequent chapters.

In contrast to his friend Allen Ginsberg, who oftimes embraced popular culture, Burroughs had little interest in the contemporary scene. That didn’t mean he couldn’t appreciate the rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle. “He didn’t know much about music, but he did know about the stage,” James Grauerholz says.[17] “And he knew about backstage. And he knew something about life in the caravan, going down the road to the next theater.” So did the acts on the original Lollapalooza tour in 1991, which brought punk, goth, metal, industrial, and gangster rap together under the new banner of alternative. In its initial run, the traveling festival boasted an anything-goes spirit that was soon exorcised by commercial forces. These days, Lollapalooza is a single-site honeypot for marketers at which bands also happen to play. (Control really should think about investing in a music festival.)

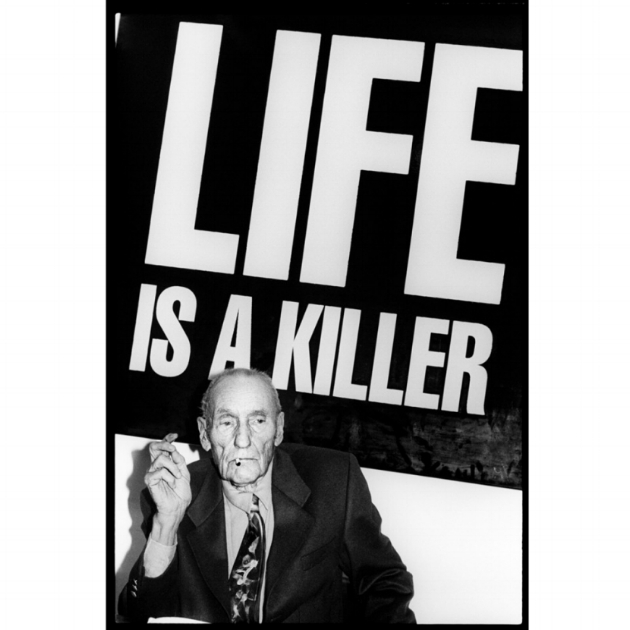

1991 also saw the release of David Cronenberg's film adaptation of Naked Lunch. That movie took considerable liberties with the source material, but nevertheless infected a whole new generation of would-be subversives with the Burroughs bug. The author himself was aware of his growing influence, though he had limited interest in serving it. “He was a mirror in which others would see themselves reflected in his work,” Grauerholz says. “He didn’t create his icon, but he certainly knew how to dress for a photoshoot.”[18] There are numerous pictures of the author with well-known musicians like Patti Smith, Mick Jagger, David Bowie, and Cobain, to name just a few. Despite being old enough to be their grandfather, Burroughs doesn’t look out of place in a single one of them.

Come as You Are

Nirvana’s serrated riffs and pockmarked melodies had little competition in the 1990s singles charts, especially compared to acts like Paula Abdul and Bryan Adams. The band’s songs packed plenty of catchy hooks, but their attitude was punk all the way. Nirvana’s debut, Bleach, made them instant heroes on the underground when it was released by indie kingmakers Sub Pop Records in 1989. Yet the band’s searing club performances and support from college radio failed to move the mainstream needle. Cobain and co. aimed for the fencesmade their play for the big leagues when Nirvana signed to Geffen Records for their next release, Nevermind. The gambit worked, and the remainder of Cobain’s short life would be spent negotiating his sudden and overwhelming success. Everyone now seemed to want something from the art-obsessed kid who never felt wanted.

Like Burroughs, who happily received accolades but spurned expectations, Cobain sought validation even as he bristled at fame. Of course, Burroughs’ experience of success was very different to Cobain’s. For much of his life, the writer was an enigma in exile, El Hombre Invisible. By contrast, Cobain felt the spotlight acutely, with the demands of his audience and handlers resulting in a persistent feeling of walls closing in. Those closest to Cobain did their best to banish thoughts about him not being long for this world, a view he likely shared. Burroughs’ friends felt similarly at certain points in the author’s life. It’s why James Grauerholz brought him to Kansas—to keep him away from temptations that would otherwise do him in.

In the fall of 1993, Cobain saw Burroughs as something more than a dispenser of obscure junkie wisdom. By virtue of the fact that he’d survived, the wan 79 year-old offered a glimmer of hope to the cherubic superstar. Here was someone who had experienced the ravages of addiction and notoriety and come out the other side, integrity intact. “It was, ‘OK, I’m in this situation but I can last, I can get through,’” says Alex MacLeod, Nirvana’s tour manager and Cobain’s close friend.[19] A year before their Kansas meeting, Cobain sought out Burroughs to work on a project that he described in his personal journal. “I’ve collaborated with one of my only Idols William Burroughs and I couldn’t feel cooler,” Cobain wrote.[20] Their collaboration, The Priest, They Called Him, was released in 1993 on a 10-inch vinyl picture disc, which today fetches premium prices in the collector’s market. The two-song set features Cobain’s junk-sick guitar weaving webs of feedback around Burroughs’ laconic croak to arresting affect. Though the pair would later meet in person, their parts were recorded separately: Burroughs at Red House Studios in Lawrence in September 1992; Cobain in November the same year at Laundry Room Studios in Seattle.

The Priest, They Called Him had roots in a previous collaboration with filmmaker Gus Van Sant, called Burroughs: The Elvis of Letters. Released in 1985 on Tim/Kerr Records, the EP features Burroughs’ spoken vignettes backed by Van Sant on guitar, bass, and drum machine. Surprisingly tuneful, it demonstrates, if nothing else, that the director might have made a serious go at indie rock. The label behind the Van Sant record was co-run by the recently departed Thor Lindsay, who played an instigating role in the Cobain-Burroughs project. “Thor was the one who said, ‘maybe we should do something with Kurt,’” Grauerholz recalls. “And he was actually the middleman. That’s how we did the tape swaps before the actual meeting.”[21]

The combination of Cobain’s guitar novas and Burroughs’ tremulous rasp taps a vein of unease. Taken together, the musical mangling of “Silent Night” and the track “Anacreon in Heaven” tell a grim tale of a junkie priest trying to score on Christmas Eve. Burroughs’ spoken parts were taken from Exterminator!—a short story collection originally published in 1973. With its abrasive sound and bleak subject matter, the record failed to light up the Christmas sales charts. Still, it is an enduring testament to Burroughs’ cross-generational appeal. It also highlights the author’s unparalleled ability to convey the the grimness of addiction. “Then it hit him like heavy silent snow,” Burroughs wearily utters. “All the gray junk yesterdays. He sat there and received the immaculate fix. And since he was himself a priest, there was no need to call one.”[22]

Around this time, Cobain was anguishing over Nirvana’s second effort for Geffen Records, the anguished In Utero. The label almost refused to release the album due to concerns over commerciality; this was a serious blow to the songwriter’s confidence. Bright spots were few in Cobain’s world in those days, and Burroughs comprises at least two of them—the trip to Lawrence and their earlier collaboration. Cobain loved The Priest, They Called Him because it was so out there and abrasive—the kind of thing that could only be released on an independent label. There was no way this music would find favor with the jocks he castigated with lyrics like: He’s the one / Who likes all our pretty songs / And he likes to sing along / And he likes to shoot his gun / But he don’t know what it means.[23]

Cobain’s fascination with Burroughs had begun years earlier. The author’s entire universe stood in stark contrast to the everyday world of the banker, the schoolteacher, or the laid-off logger. Burroughs’ exotic escapades in far-flung places like Morocco looked irresistible to a young man on a go-nowhere track. Cobain initially discovered Burroughs as a teenager, furtively reading dog-eared library copies of Naked Lunch and Junkie in between ditching class and experimenting with drugs and alcohol. It wasn’t just a lifestyle crush; he was also taken by Burroughs’ pioneering work with cut-ups. Burroughs developed the technique in collaboration with visual artist Brion Gysin in a Paris hotel in 1958. The method is simple: take some text and slice it into quarters with scissors or a razor blade, then randomly reassemble the pieces. Burroughs believed cut-ups were a more accurate portrayal of reality, if not a byproduct of our very existence. “Consciousness is a cut-up,” he explained in a 1986 collection of essays, The Adding Machine. “As soon as you walk down the street, or look out the window, turn a page, turn on the TV—your awareness is being cut,” he said. “That sign in the shop window, that car passing by, the sound of the radio. . . Life is a cut-up.”[24]

In an interview shortly after “Smells Like Teen Spirit” catapulted Nirvana into the mainstream, Cobain referred to Burroughs as his favorite author and called the cut-up approach “revolutionary.” On the 1991 European tour for Nevermind, Cobain’s sole piece of luggage was a small bag containing Naked Lunch, which he had recently rediscovered at a used bookshop in London.[25] Cobain was such a fan that he asked Burroughs to appear as a crucifixion victim in the video for “Heart Shaped Box.” In a 1993 letter to Burroughs, Cobain came across as sincere and respectful: “I wanted you to know that this request is not based on a desire to exploit you in any way,” he wrote. “I realize that stories in the press regarding my drug use may make you think that this request comes from a desire to parallel our lives. Let me assure you that this is not the case. As a fan and student of your work, I would cherish the opportunity to work directly with you.”[26] In his personal journals, Cobain described his vision for the video:

William and I sitting across from one another at a table (black and white) lots of Blinding Sun from the windows behind us holding hands staring into each others eyes. He gropes me from behind and falls dead on top of me. Medical footage of sperm flowing through penis. A ghost vapor comes out of his chest and groin area and enters my Body.[27]

Burroughs declined the offer—he would not be depicted as dying on film—but he did give Cobain a standing invite to visit him in Lawrence.

On a sunny day in October 1993, Cobain—just three days into the American tour for In Utero—arrived at Burroughs’ Lawrence home on 1927 Learnard Avenue. With a population of nearly 70,000, Lawrence was far larger than the Aberdeen, Washington of Cobain’s youth, where there were more trees than people. Cobain was already familiar with the city, having performed there with his band shortly before they broke in the mainstream. His Lawrence visit offered brief respite from the treadmill-like existence of a superstar who at that time wanted to be anything but. Exhausted, addicted, and struggling with the unasked-for appointment as the “voice of a generation,” Cobain desperately needed the breather.

Tour manager Alex MacLeod drove Cobain to meet the old man following Nirvana’s performance at Memorial Hall in Kansas City. “I called his room and he’s already ready to go,” MacLeod says. “I recognize this is completely different than any other day, because there’s no prodding. There’s no ‘come on, you’re killing me here.”[28] Cobain was not the kind of person to telegraph elation at the best of times; in the depths of narcotic numbness and depression, he was even more remote. But this day was different. “ He was quite excited, and he was nervous,” MacLeod recalls. “He was meeting someone who he had an immense respect for as a writer. Burroughs was this artist who covered so many mediums and it’s what Kurt wanted to be. He saw himself as someone who could create in different mediums as he did with his paintings, drawings, his writing, music and everything else.”

Giddy with anticipation, but trying his best to be cool, Cobain stepped along the narrow walkway leading to the cozy porch of 1927 Learnard. “William opened the door and greeted Kurt,” MacLeod describes. “I mean, he was a real gentleman, we went through and sat down, talked, and tea was made. Then the two of them went off and talked and did the whole tour—ya know, the typewriter, and the rest, the two of them wandering around the house together and then outside.” Their rapport was genuine. “William made him feel at ease very quickly. There was definitely a connection on an artistic level. I think William saw a lot more in him than Kurt even realized.”

Burroughs recognized a deeply troubled soul. “As we were about to leave the room, William said to me, ‘your friend hasn’t learned his limitations and he’s not going to make it if he continues,’” MacLeod remembers. “I think he saw himself at a certain point in his own life maybe, or someone who was very similar in many ways. At a certain point he could have gone in one direction and it all would have been lost. With Kurt, he saw this kid moving in that direction very quickly. It was meaningful the way William interacted with him and how he welcomed Kurt and myself into his home and kind of guided him around his world. I think William understood his position. . . it’s maybe why he voiced his concern.”

Scentless Apprentice

Thirty-five years and two months prior, in July of 1958, Burroughs found himself face-to-face with an older artist he greatly admired, Louis-Ferdinand Céline. Alongside lifelong friend and onetime romantic obsession Allen Ginsberg, Burroughs journeyed to Meudon, a suburb of Paris where Céline and his bevy of dogs resided. Céline’s home, like Burroughs’ later Lawrence spread, was painted red and set back from the road. By this point, Céline, who was also a physician, lived a solitary life, muttering and cursing about whomever had crossed him recently or in the distant past. Burroughs and Ginsberg were greeted by ferocious barking until a lanky and disheveled figure appeared and cajoled the dogs into something resembling calm. Of the animals, Céline remarked, “I just take them with me to the Post Office to protect me from the Jews.” Despite his prejudices, Céline was regarded as a Titan of French letters, whose misanthropic yet blackly humorous prose delighted Burroughs and Ginsberg.

The trio settled in for conversation in a manicured spot of yard outside the house. Céline prattled at length about those who had slighted him, his experiences of prison, and how the neighbors were trying to poison his dogs. When the conversation shifted to his work as a physician, Céline expressed a cynical kind of job satisfaction, saying, “Sick people are less frightening than well ones.” To which Burroughs retorted, “and dead people are less frightening than live ones.”[29] When asked about literary contemporaries, Céline didn’t hesitate to dismiss other writers and countrymen such as Jean Genet, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Henri Michaux as “just another little fish in the literary pond.”[30]

Burroughs and Ginsberg departed with the sense that Céline, while brilliant, had little time for anyone but himself—least of all a pair of young writers from an insurgent American literary movement. Burroughs and Ginsberg nevertheless enjoyed their visit, which they found both amusing and legitimizing. It’s possible that Burroughs’ tolerance for the younger artists who later came to pay their respects was informed by his own experiences with figures like Céline. Then again, it might have just been good manners.

He Likes to Shoot His Guns

Cobain’s meeting with Burroughs lasted a handful of hours, during which the two exchanged presents—Burroughs gave Cobain a painting he’d made, and the musician gifted the author a signed biography of Leadbelly, whom Cobain claimed he discovered from reading an interview with Burroughs. He also presented a large, decorative knife that was more art piece than weapon, which Burroughs later gave to his Lawrence friend Wayne Propst.[31] Cobain gamely explored Burroughs’ orgone accumulator—a coffin-like box built from a design by Austrian psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich that was meant to capture a potent yet elusive energy called orgone. Inside this unhandsome plywood apparatus, Burroughs would bathe in the “universal life force” first posited by Reich in 1939. A pariah of the medical establishment, Reich died in prison in 1957, sent there by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for committing “fraud of first magnitude,” which included claims that the device cured cancer.[32] For his part, Burroughs often said that the orgone accumulator was a substitute for orgasms (which might make sense given that the junkie libido is next to nonexistent). Still, the box was not without its risks. “Warning—misuse of the Orgone Accumulator may lead to symptoms of orgone overdose. Leave the vicinity of the accumulator and call the Doctor immediately,” read the label posted on Reich’s personal contraption.[33]

Cobain entered the box and posed for a photo with a rare grin breaking across his face. Maybe it was the orgone. MacLeod has another theory. “The focus wasn’t him,” he says. “He was obviously happy. He was invigorated; he’s smiling. And ya know, that didn’t happen too often at that point.” On the ride back to meet the tour, Cobain was chattier than usual, even effusive. “He was talking about the pieces of art he’d seen, the orgone accumulator and the rest,” MacLeod remembers. Cobain was deeply touched that Burroughs had accepted him as a fellow artist. “I think he was kinda in awe that he was treated as an equal by this person he had perceived as being ya know. . . elevated,” MacLeod recalls.

Burroughs’ impressions of Cobain were touchingly earnest. As he later recalled: “Cobain was very shy, very polite, and obviously enjoyed the fact that I wasn’t awestruck at meeting him. There was something about him, fragile and engagingly lost. He smoked cigarettes but didn’t drink. There were no drugs. I never showed him my gun collection.”[34]

Burroughs was a lifelong firearms enthusiast who felt stymied by handgun restrictions in New York City, where he lived from 1974 to 1981. In Lawrence, he was able to build a small arsenal that included several shotguns, a Colt .45 and a .38 Special. Thurston Moore, then-vocalist and guitarist for New York City noise-rock heroes Sonic Youth, who met Burroughs in the early ’90s, described the scene: “I recall sitting in his living room and he had a number of Guns and Ammo magazines laying about and he was only very interested in talking about shooting and knifing. . . I asked him if he had a Beretta and he said: ‘Ah, that’s a ladies’ pocket-purse gun. I like guns that shoot and knives that cut.’”[35]

Burroughs’ only real competition in the literary legend/firearms freak department was Hunter S. Thompson, who in the mid-1990s drove down from his Woody Creek, Colorado compound—his candy-apple red 1971 Chevy Impala loaded with drugs, guns, and ammo—for two days of blasting at targets with Burroughs. In between sessions, the famously gonzo Thompson raised hell throughout Lawrence, but he dialed it back considerably in the presence of the older author. As Jim McCrary later said, “We managed the final few blocks to William’s house. And then something amazing happened. Dr. Thompson switched gears. The minute he walked into the house his demeanor, his energy, his self became as quiet and attentive as a student before the master.”[36] Thompson gave Burroughs a one-of-a-kind 454-caliber pistol. “It did back him up at least five feet,” McCrary said. “When the smoke cleared there was a rivulet of blood trickling down William’s thumb and wrist. ‘Son of a bitch bit me,’ he giggled.”

Burroughs’ relationship to guns—he was an avid shooter, but never hunted—was greatly complicated by the tragic killing of his wife. Though the incident was ruled an accident, the rest of the author’s life was spent privately interrogating his role in her death. Joan Vollmer, a poet and fellow drug user, was Burroughs’ constant companion in the years leading up to his emergence as a writer. She was also a key player in the early Beat movement, albeit behind-the-scenes. Her flat on 100th and Broadway in New York was a gathering place for the emerging heroes of the new literature, including Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Neal Cassady. The Beat movement was very much a boys’ club, but Vollmer was respected for her razor-sharp wit, which intertwined with Burroughs’ dyspeptic asides to such an extent that outsiders had a hard time keeping up with their repartee. The poet and street hustler Herbert Huncke, who gave Burroughs his first heroin fix and coined the term Beat, claimed the pair was, “very witty with a terrific bite, almost vitriolic with their sarcasm. They could carry on these extremely witty conversations. . . I couldn’t always understand them, and it used to make me feel sort of humiliated because I obviously did not know what they were talking about.”[37] As Kerouac, author of On the Road, Dharma Bums and Desolation Angels, put it, “She loved that man madly, but in a delirious way of some kind.”[38]

On the evening of September 6, 1951, William S. Burroughs, 37, and Vollmer, 27, were three sheets to the wind at friend John Healey’s apartment on 122 Monterrey in Mexico City, above a bar popular with Burroughs and the coterie of expats at Mexico City College where he studied Mayan archeology. The late summer heat was oppressive, as was the sour mood that had settled over the festivities. Vollmer was nearly as drunk her husband; the Benzedrine she’d been popping for years was difficult to obtain south of the border, so she relied on swigs of tequila for the majority of her waking hours.

As daytime bled into a thick and humid evening, Joan compulsively rolled an empty glass tumbler between her palms while making the occasional snide remark about Burroughs’ recent “honeymoon” in the South American jungle with his then-romantic obsession Lewis Marker, a 21 year-old American boy from Jacksonville, Florida. His attempted fling with Marker wasn’t the only reason for the trip. Burroughs was in pursuit of a botanical hallucinogen called yage, which he describes in the novel Queer, written between 1951 and 1953, but not published until 1985. “He had these different properties in East Texas and South Texas, and it is immediately concurrent with the sale of these properties that he turns to Lewis and said, ‘hey, let’s go on a trip to South America and take this yage stuff,” James Grauerholz says. “Because he had money. He said, ‘I’ll stash the old lady and the kids and you and me will go, and we’ll find it.’ Well, they didn’t, as you can see at the end of Queer.”[39]

The romantic part of the trip didn’t go very well, either. Marker was a reluctant sexual partner, being by and large heterosexual. Nevertheless, Burroughs wouldn’t drop the idea of taking the family—Marker included—to Ecuador, where they’d live off the land. On the night of her death, Vollmer, having endured Burroughs’ failed farming efforts in Texas and legal troubles in New Orleans, verbally dismissed the plan in front of Marker and his school pal from Jacksonville, Eddie Woods, the only other witness. “I think it’s about time for our William Tell routine,” Burroughs is said to have replied. According to witness accounts, Vollmer then positioned the shot glass atop her unkempt hair, which was thinning due to a combination of stress, a recent bout with polio, and the long-term effects of alcohol and amphetamine addiction. Burroughs, known to friends as a crack marksman, steadied his aim and fired. Vollmer slunk to the floor, a single bullet hole in the left side of her forehead.

Something In the Way

The story of how Burroughs, Vollmer, her daughter from a previous marriage and their infant son, William S. Burroughs, Jr., ended up in Mexico City is one of desperation, criminality, and plain bad luck. In November 1946, the family ditched New York City for south Texas, where Burroughs made what would turn out to be an ill-fated foray into vegetable and marijuana farming. Burroughs had recently kicked a heroin habit that precipitated the family’s flight from New York under a cloud of legal hassles and psychological strain—Burroughs had been pegged for prescription forgery and Vollmer had recently been released from Bellevue Hospital, where she had been placed under observation for erratic behavior. Burroughs’ escape to Texas was in some ways an attempt to prove to his parents that he could provide for his family without their monthly allowance of around two hundred dollars (a tidy sum that he continued to accept until age 50). For their part, the long-suffering Laura and Mortimer (“Mote”) Burroughs were thrilled to see their son turn his back on hard drugs and petty crime.

The family settled into the ramshackle spread along with their fast-talking hustler of a “farmhand,” Herbert Huncke, who also played the role of nanny and drug courier. Biographer Ted Morgan wrote of Burroughs and Vollmer’s relationship following extensive interviews with Huncke in the 1980s:

They slept in separate rooms, and there seemed to be no physical contact between them. One night when [Huncke] was trying to sleep he heard Joan knock on Burroughs' door. When the door opened, Huncke heard her say, "All I want is to lie in your arms a little while." [...] Once they were walking in the woods and Joan was tiring from carrying Julie and Huncke said "Why don't you fuckin' help her," and Burroughs responded that the Spartans knew how to deal with the excess baggage of female infants by throwing them off cliffs. [...] [Huncke felt] that kind of sardonic humor was Burroughs' way of coping with emotions, but [he] never got used to it. On the other hand, if anyone criticized Joan, Burroughs came to her defense. When Huncke said that she was a little extravagant in her shopping, Burroughs said, "Well, after all, she wants to see that we're fed properly." He never said anything about her benzedrine habit.

By October, the marijuana yield was ready. This was to be Burroughs’ big financial windfall. He persuaded the family—including Huncke and the two tots—to head back to New York City, where they could find buyers for the pot that Burroughs, Huncke, and Vollmer stuffed into mason jars and loaded into duffel bags. With the trusty jeep packed with what Burroughs assumed was primo tea, he and Huncke drove straight through to New York, with Vollmer and the kids traveling separately by train. But Burroughs had forgotten an essential step in the cultivation of marijuana: the curing process. Turns out all that pot had next to no value as an intoxicant, a fact that Burroughs discovered when he tried to find his first buyer. Making matters worse, Burroughs and Huncke arrived in New York to find Joan and the kids had been picked up by police at Grand Central Station, on suspicion that she was about to abandon them. Vollmer was once again held at Bellevue mental hospital for observation; Burroughs sprung her by showing off his Harvard Club membership and making vague intimations of social standing.[40]

Unable to find buyers for the botched crop, Burroughs kicked around the city for a few weeks, picking up another junk habit and trying to avoid the cops. His time in New York—originally as one of the criminals, oddballs, and dropouts hovering around Vollmer’s apartment, and now as a desperate addict with two kids—would come to be chronicled in Junkie, a terse, reportorial novel that would later captivate artists from Lou Reed to Hüsker Dü. Burroughs was always drawn to the seedier side of life. As a young man, he was smitten with the switchblade slang of You Can’t Win, the autobiography of 1920s hobo burglar Jack Black. The book’s drug depictions mirror Burroughs’ own accounts of addiction. “It was the small, still hours of the night that got me,” Black wrote. “Opium, the Judas of drugs, that kisses and betrays, had a good grip on me, and I prepared to break it.”[41]

In addition to the killing of Vollmer, Burroughs’ criminal history included prescription forgery, petty theft, possession of narcotics, and simply being a gay man in America in the days before Lawrence v. Texas. In some ways, his behavior can be seen as an attempt to transform himself into something other than an upper middle class nobody, even if the attention received was negative. Many of his hijinks were harmless. Burroughs liked to rope his friends into “routines”—a form of play-acting that often featured characters and situations that would later turn up in his work. He was obsessed with capturing these routines, which he saw as a potent means of making things happen in the real world. They were a way to record his fantasies, obsessions and animosities—the cornerstones of his work—when no other means were available. Also, they were great fun. Regular participants included Columbia University freshman Ginsberg and the the ruggedly handsome Kerouac, former college football star and onetime Merchant Marine. Burroughs, Ginsberg, and Kerouac form the triumvirate that would go on to transform American literature and inspire a revolution in youth culture. But even before a single book or poem was published, there was trouble.

It was 1944, the final stretch of World War II—a tense time in America, given that Allied victory was hardly guaranteed. Nevertheless, life went on, especially in New York. The city was aflame with passion and plight. There was jazz in the clubs, junk in the streets, and G.I.s looking for a good time before they shipped out. Lucien Carr, the precocious Puck of Burroughs’ social set, was a nineteen year-old college student in an intense friendship with David Kammerer—a teacher from St. Louis who had earlier grown infatuated with the young man, going as far as to follow him to New York. The two were close friends, but Carr had become increasingly put off by Kammerer’s persistent sexual advances. On August 13, their dynamic turned deadly. Stumbling drunkenly along the shores of Riverside Park in the early morning hours, Carr fatally stabbed Kammerer, hastily dumping the body in the Hudson. Panicked, the young man then turned to his closest friends: Kerouac and Burroughs. Kerouac stood watch as Carr buried the murder weapon, and was later arrested as a material witness to the crime. Burroughs, too, was picked up after Carr went to his apartment and handed him a pack of Kammerer’s bloody cigarettes. Burroughs promptly flushed them down the toilet, advising Carr to find a good lawyer and turn himself in. Carr eventually went to the District Attorney and made a confession. He served two years for second-degree murder, and largely kept his nose clean upon release.

Many years later, in 2013, the Carr-Kammerer affair was made into a not-very-good movie, Kill Your Darlings, the best part of which is Ben Foster’s low-key portrayal of Burroughs. Overall, the tale reminds of the 1990s Norwegian black metal scene in which a member of the group Mayhem murdered a bandmate in an impulse killing with homophobic overtones—an ugly incident that is also being made into a movie. For whatever reason, people are fascinated by the violent shared histories of small cliques whose leaders have artistic ambitions. At the very least, it explains the ongoing fascination with Charles Manson.

By January 1948, Burroughs had more than a few reasons to want to leave the traps and temptations of New York City. The killing of Kammerer weighed heavy on everyone in their social circle. And Burroughs had picked up a a raging junk habit that he desperately wanted to kick. Rehab clinics were few and far between, and most were brutal. The junkie’s choice for recovery at the time was the notorious “federal narcotics farm” in Lexington, Kentucky, where patients could get their fill of opiates in exchange for signing on to an experimental drug program run by the U.S. government. Burroughs first attempted to wean himself off heroin while driving to Texas, where he intended to get back to the farm life. He had previously attempted a self-administered cure, but that didn’t take, so Burroughs made made a beeline for Kentucky and the strangest rehab facility in North America.

The Clinical Research Center of the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital in Lexington opened its doors to neuropsychiatric patients in 1935, after which it became a top-secret CIA facility where drugs like LSD were tested on hapless patients.[42] Junkies were provided whatever they wanted so long as they consented to be dosed with industrial-grade psychostimulants, which the spooks believed held the key to programmable assassins and the flipping of enemy agents.[43] Burroughs did not take part in this program, choosing instead the regular ten-day regimen of dose reduction. Lexington was a popular rehab facility for musicians, as well—jazz musicians Chet Baker and Sonny Rollins also cleaned up at the facility. Burroughs’ time at Lexington is matter-of-factly chronicled in Junkie, where he describes the effects of heroin addiction and recovery:

Junk turns the user into a plant. Plants do not feel pain since pain has no function in a stationary organism. Junk is a pain killer. A plant has no libido in the human or animal sense. Junk replaces the sex drive. Seeding is the sex of the plant and the function of opium is to delay seeding.

Perhaps the intense discomfort of withdrawal is the transition from plant back to animal, from a painless, sexless, timeless state back to sex and pain and time, from death back to life.

Having broken free from the grip of junk, Burroughs and his family next put down stakes in New Orleans. He was rid of the Texas farm by June 23, 1948, at which point, he’d already been living with Vollmer and the kids at a rooming house on 111 Transcontinental Drive in New Orleans. Shortly thereafter, they settled across the river in Algiers, in a house at 509 Wagner Street purchased with financial assistance from his parents. Burroughs’ time was largely spent drinking and chasing young men. He managed to keep off heroin however, mostly because he wasn’t able to decode the rules of the New Orleans junk scene. Sex was easier to come by. “In the French Quarter there are several queer bars so full every night the fags spill out onto the sidewalk,” he said.[44]

Eventually, he managed to get himself strung out with the help of local addict Joe Ricks (referred to as “Pat” in Junkie). Early in the New Year, Jack Kerouac visited and found Burroughs in such a state of disarray that he split after about a week, having had his fill of the household’s slovenliness. He was also put off by Vollmer’s woebegone appearance—sallow eyes, puffy face, and beset with a limp from her polio bout. By April 1949, Burroughs found himself in trouble with the law yet again, getting arrested when his strung-out associates were busted driving his car, prompting a search of the Wagner St. house, where cops found contraband and a few handguns. Burroughs’ parents once again bailed him out, but he’d already grown tired of what he perceived to be draconian law enforcement in America. Vollmer described the situation in a letter to Kerouac, dated April 13, 1949:

I don't know where we'll go—probably either a cruise somewhere or a trip to Texas to begin with— After that, providing Bill beats the case, it's harder to say. New Orleans seems pretty much out of the question, as a second similar offense, by Louisiana law, would constitute a second felony and automatically draw 7 years in the State pen. Texas is almost as bad, as a second drunken driving conviction there would add up to about the same deal. N.Y. is almost certainly out—largely because of family objections. . . It makes things rather difficult for Bill; as for me, I don't care where I live, so long as it's with him.

Vollmer and the kids ended up following Burroughs to Mexico. In the months before her death, she slipped further into alcoholism, her once alluring face aged well beyond her 27 years. Burroughs initiated his ill-fated romance with Lewis Marker and raised hell at area watering holes. His troubled wife tended to their children to the best of her ability in between gulps of tequila.

By spring of 1951, Burroughs had taken his loco schtick too far on more than one occasion, even having his firearm taken away by a Mexican cop for brandishing it drunkenly at bar patrons. It seems that Burroughs was more out-of-control on booze than junk. Could it be that the William Tell incident would not have happened had he been strung out? There were ominous clouds on the horizon well before the fatal evening. Lucien Carr showed up with Allen Ginsberg in August; some believe that Vollmer filed for divorce after a brief fling with Carr. Burroughs and Vollmer quickly reconciled, and he stuck to the claim that he and Joan suffered no real marital strife. That is, besides the fact that he was a homosexual drug addict and she an alcoholic with lingering health problems as a result of benzedrine abuse. Still, whatever connection they had at the outset of their relationship—that telepathy Vollmer so affectionately noted—remained intact right up to her death.

Carr’s visit, which took place while Burroughs was on his jungle adventure with Marker, was as much a provocation as a reunion. The behavior he describes in Howard Brookner’s Burroughs: The Movie (1983) is as irresponsible as any involving rock ‘n’ roll animals like Lou Reed or Jim Morrison. “Joan and I were drinking and driving so heavily that at one point we could only make the car go if I lay on the floor and pushed on the gas pedal, while she used her one good leg to work the brake and clutch,” Carr said. “It was a pretty hairy trip, but Joan and I thought it was great fun. Allen I don't think did, and surely the kids didn't.” Ginsberg recalled, “He [Carr] was going around these hairpin turns and she was urging him on saying, ‘How fast can this heap go?’—while me and the kids were cowering in the back.”

It is tempting to see Vollmer’s behavior with Carr as a death wish; one of a finite series that ended with a shot from her husband’s pistol. It is a view that Ginsberg advanced as a way of making sense of the killing. “I always thought that she had kind of challenged [Burroughs] into it. . . that she was, in a sense, using him to get her off the earth, because I think she was in a great deal of pain,” he said.[45] Burroughs did not accept Ginsberg’s rationalization, telling biographer Morgan in the 1980s, “I’ll never quite understand what happened. Allen was always making it out as a suicide on her part, that she was taunting me to do this, and I do not accept that cop-out. Not at all. Not at all.”

Loss can drive people to embrace all kinds of questionable ideas. Look no further than obsessive Kurt Cobain fans who truly believe Courtney Love hired someone to kill him. It is perhaps unsurprising that Burroughs’ friends, lovers, colleagues, biographers, and readers would attempt to divine meaning from a cruelly senseless act. And yet, for all the speculation, we are no closer to truly understanding the underlying motivation—if any—behind Burroughs’ shooting of a woman whom by all accounts was an ally and partner.

In 1953, Burroughs wrote to Ginsberg, addressing an odd moment with his childhood friend Kells Elvins, who was also kicking around Mexico City around the time of the tragedy. “Did I tell you Kells' dream the night of Joan's death?” Burroughs wrote. “This was before he knew, of course. I was cooking something in a pot, and he asked what I was cooking and I said ‘Brains!’ and opened the pot, showing what looked like ‘a lot of white worms.’” The extent of Burroughs’ culpability eluded the man him. As he said to Ginsberg in the same letter: “One more point. The idea of shooting a glass off her head had never entered my mind consciously, until—out of the blue, as far as I can recall—(I was very drunk, of course), I said: ‘It's about time for our William Tell act. Put a glass on your head, Joan.’ Note all those precautions, as though I had to do it, like the original William Tell. Why, instead of being so careful, not give up on the idea? Why indeed? In my present state of mind, I am afraid to go too deep into the matter. I aimed carefully at six feet for the very top of the glass.”

All Apologies

Chaos and confusion greeted the aftermath. Burroughs changed his story at least four times, and the newspapers had a field day. Burroughs’ brother Mort Jr. came down and irritated all his friends. The slick lawyer representing his case, Bernabé Jurado, was well suited to Mexico City’s culture of bribery and graft. Did Burroughs’ parents pay to get him off the hook? James Grauerholz concludes that, while Burroughs’ parents likely spent considerable cash to influence everyone from ballistics experts to arraignment officials, it didn’t necessarily impact the verdict.[46] Burroughs’ sentencing falls within a range common not only in Mexico, but also in many parts of the United States. Still, a two-year suspended sentence seems light given the severity of the crime. That doesn’t mean Burroughs didn’t suffer for his actions. In fact, he continued to be haunted by Joan’s death right up until his own. On July 27, 1997, he referenced Joan in his journal, just five days before his passing. His regrets are plain: “Why who where when can I say—Tears are worthless unless genuine, tears from the soul and the guts, tears that ache and wrench and hurt and tear. Tears for what was—”[47]

In being charged with manslaughter in absentia, William S. Burroughs dodged serious punishment that might have deprived the world of a powerful literary voice. And yet his complicity in Vollmer’s death is inescapable even if the act was unintentional. But what if intention doesn’t matter? Burroughs was still guilty of committing the action. “In the magical universe there are no coincidences and there are no accidents,” he said.[48] A bullet leaves the chamber and narrowly misses its target. The tape machine replays the loop: forward, backward; backward, forward. The bullet re-enters the chamber from the barrel end. A gaunt man cocks his eye and takes aim. Again, the reel clatters, the scene unfolds. Backwards. Forwards. The gun is steadied. The woman turns her head. A shot rings out.

Kurt Cobain’s life was punctuated by shots—a procession of needles then a single blast from a hastily obtained firearm. In a grim foreshadowing of his own end, Cobain’s last photo session in Paris depicted him with a handgun to his mouth, which was apparently his own idea. The pictures, captured in February 1994, sit uncomfortably with those from a few weeks later, when the world glimpsed Cobain’s sneakered foot peeking out from the greenhouse of his Lake Washington home, his life cut short by what investigators concluded was a self-inflicted shotgun wound to the head.

Would Cobain have made different choices had he not encountered Burroughs? Junkie—originally published in 1953 under the pseudonym William Lee—remains the gold standard heroin reportage. The book and its author have been accused of glamorizing addiction, a charge Burroughs consistently rejected. As friend and collaborator Victor Bockris says, “He imagined a way of living that he tried to pass on in his books, and he tried to live it as closely as he could.”[49] Cobain cops to Burroughs being among his inspirations for trying heroin. “Maybe when I was a kid, when I was reading some of his books, I may have got the wrong impression,” Cobain said. “I might have thought at that time that it might be kind of cool to do drugs. I can’t put the blame on that influence but it’s a mixture of rock ’n’ roll in general—you know, the Keith Richards thing and Iggy Pop and all these other people who did drugs.”[50]

In an attempt to fathom his own motivations for using, Burroughs explored “the algebra of addiction,” his term for the myriad equations of dependency. “The questions, of course, could be asked: Why did you ever try narcotics?” he wrote in Junkie. “Why did you continue using it long enough to become an addict? You become a narcotics addict because you do not have strong motivations in the other direction.”

Cobain had “motivations in the other direction,” his wife and infant daughter among them, but for whatever reason they weren’t enough. It’s easy to blame childhood trauma, addiction, and the pressures of fame for his decision, which isn’t entirely spelled out in the sweet and rambling suicide note he left. There is little use wondering where his talents might have taken him had he remained above ground. We will never know. Burroughs managed to survive, producing a mountain of work that has captured the imaginations of artists well before and well after Cobain. But who is the man behind the icon? Does the character that Kurt Cobain, Patti Smith, David Bowie, Lou Reed, Thurston Moore, and many more admired have anything in common with the real William S. Burroughs? That’s what we’ll find out.

Burroughs’ relationship to music was like a centipede trapped in amber, that is to say frozen in time. When compiling the soundtrack for Burroughs: The Movie, Grauerholz wanted to feature songs that Burroughs knew and enjoyed. He worked with Hank O’ Neal, an accomplished music producer, author, photographer and onetime CIA agent, to assemble the material. O’Neal ended up making a couple of cassette tapes for Burroughs for his own use. “We used to listen to them on the trip to the methadone clinic,” Grauerholz says. The cassettes featured popular artists of yesteryear, including Wendall Hall and Max Morath. “These cold, grey mornings. . . he’s just woken up and sniffling. We’d listen to these tapes, and it would come up to something from the 1920s, like, ‘please don’t be angry, ’cause I was only teasing yooooou.’ And that was originally a 78. He had a Victrola. He really was a creature of the 19th century.”[51]

With tastes like these, Burroughs was not Nirvana’s target demographic. Still, he maintained a soft spot for the band’s leader. For Cobain’s 27th birthday on February 20, 1994, Burroughs sent a photo of Kurt inside the orgone accumulator affixed to a painting he had made himself. A note in cramped handwriting read: “For Kurt, all best on 27th birthday and many, many more. From William S. Burroughs.” Less than two months later, the young star was dead. In the wake of the tragedy, Burroughs reflected on their meeting and Cobain’s choice to end his life. “The thing I remember about him is the deathly grey complexion of his cheeks,” he remarked. “It wasn’t an act of will for Kurt to kill himself. As far as I was concerned, he was dead already.” [52]As Christopher Sandford describes in the biography Kurt Cobain, Burroughs, troubled by the musician’s violent end, attempted to find meaning in Kurt’s lyrics: “There was surely poignancy in the sight of the 80 year-old author, himself no stranger to tragedy, scouring Cobain’s songs for clues to his suicide. In the event he found only the ‘general despair’ he had already noted during their one meeting.” Cobain’s suicide note demonstrates his intense feelings of empathy: “There’s good in all of us and I think I simply love people too much, so much that it makes me feel too fucking sad.”

Burroughs’ own exit would not come for several more years. He made his final journal entry on July 30, 1997—just three days before he died from complications following a heart attack. His final testament bears some similarities to Cobain’s: “There is no final enough of wisdom, experience—any fucking thing. No Holy Grail, No Final Satori, no solution. Just conflict. Only thing that can resolve conflict is love, like I felt for Fletch and Ruski, Spooner, and Calico. Pure love. What I feel for my cats past and present. Love? What is it? Most natural painkiller what there is. LOVE.”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Miles, Barry. Call Me Burroughs: A Life. New York: Twelve, 2015.

[2] Morris, Frank. "William S. Burroughs And Lawrence, Kansas: Linked Inexorably." KCUR. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://kcur.org/post/william-s-burroughs-and-lawrence-kansas-linked-inexorably.

[3] Burroughs, William S. The Adding Machine: Selected Essays. New York: Grove Press, 2013.

[4] Telephone interview by author. February 5, 2017.

[5] Miles, Barry. Call Me Burroughs: A Life. New York: Twelve, 2015.

[6] Morris, Frank. "William S. Burroughs And Lawrence, Kansas: Linked Inexorably." KCUR. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://kcur.org/post/william-s-burroughs-and-lawrence-kansas-linked-inexorably.

[7] Telephone interview by author. February 5, 2017.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Knopper, Steve. "The Grunge Gold Rush." NPR. January 12, 2018. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://www.npr.org/sections/therecord/2018/01/12/577063077/the-grunge-gold-rush.

[10] In 1992, Cobain told a Singapore publication, “Rebellion is standing up to people like Guns N’ Roses”; the same year, Axl Rose called Cobain “a fucking junkie with a junkie wife” during a Guns N’ Roses performance. Things came to a head with a testy scene backstage at that year’s MTV Video Music Awards, where Axl threatened physical violence against Cobain, though no blows were exchanged. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/guns-n-roses-vs-nirvana-a-beef-history-20160411

[11] Burroughs, William S. The Adding Machine: Selected Essays. New York: Grove Press, 2013.

[12] Burroughs attended one of Korzybski’s seminars in 1939, and in 1974, recalled being “very impressed by what [Korzybski] had to say. I still am. I think that everyone, everyone, particularly all students should read Korzybski. [It would] save them an awful lot of time.” "William Burroughs Press Conference at Berkeley Museum of Art on November 12, 1974 : William Burroughs : Free Streaming." Internet Archive. November 12, 1974. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://www.archive.org/details/BurroughsPressConf.

[13] Blake was also a noted influence on Ginsberg, who mentions him in “Howl.”

[14] “Hoodlums and riff-raff of the lowest caliber filled the highest offices of the land. When the Supreme Court overruled some of the legislation perpetrated by this vile route, Roosevelt forced that honest body, one after the other on threat of immediate reduction to the rank of congressional lavatory attendants, to submit to intercourse with a purple-assed baboon so that venerable honored men surrendered themselves to the embraces of a lecherous, snarling simian while Roosevelt and his strumpet wife and veteran brown-nose Harry Hopkins, smoking a communal hookah of hashish, watched the immutable spectacle with cackles of obscene laughter.” “Roosevelt After Inauguration,” Burroughs, William S., James Grauerholz, and Ira Silverberg. Word Virus: The William S. Burroughs Reader. New York: Grove Press, 1998.

[15] Burroughs, William Seward. The Western Lands. London: Penguin Classics, 2010.

[16] In his introduction to Queer, written in the 1950s, but not published until 1985, Burroughs opined on the death of his wife Joan Vollmer, killed by a bullet fired from Burroughs’ pistol during a drunken game of William Tell: “I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan’s death, and to a realization of the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing. I live with the constant threat of possession, from Control. So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and manoeuvred me into a lifelong struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.” [Emphasis added.]

[17] Telephone interview by author. October 28, 2017.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Telephone interview by author. February 3, 2017.

[20] Reporter, Matthew Gilbert -. "The Life and times of William S. Burroughs - The Boston Globe." BostonGlobe.com. January 25, 2014. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://www.bostonglobe.com/arts/books/2014/01/25/the-life-and-times-william-burroughs/NdXpBePErha2VEwsdnzUmN/story.html.

[21] Telephone interview by author. October 28, 2017.

[22] "William S. Burroughs & Kurt Cobain – The Priest They Called Him." Genius. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://genius.com/William-s-burroughs-and-kurt-cobain-the-priest-they-called-him-lyrics.

[23] "Nirvana – In Bloom." Genius. November 30, 1992. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://genius.com/Nirvana-in-bloom-lyrics.

[24] William S. Burroughs, The Adding Machine

[25] "William S. Burroughs and Kurt Cobain — A Dossier." RealityStudio. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://realitystudio.org/biography/william-s-burroughs-and-kurt-cobain-a-dossier/.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Smarsh, Sarah. It Happened in Kansas: Remarkable Events That Shaped History. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot, 2010.

[28] Telephone interview by author. February 3, 2017.

[29] Morgan, Ted. Literary Outlaw: The Life and times of William S. Burroughs. New York: W.W. Norton &, 2012.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Wayne Propst offers a touching and humorous account in the 2010 documentary Words of Advice: William S. Burroughs on the Road.

[32] Louv, Jason. "The Scientific Assassination of a Sexual Revolutionary: How America Interrupted Wilhelm Reichs Orgasmic Utopia." Motherboard. July 15, 2013. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/mggzpn/the-american-quest-to-kill-wilhelm-reich-and-orgonomy.

[33] Bellis, Mary. "Why Did the U.S. Government Want This Device Destroyed?" ThoughtCo. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://www.thoughtco.com/wilhelm-reich-and-orgone-accumulator-1992351.

[34] "William S. Burroughs and Kurt Cobain — A Dossier." RealityStudio. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://realitystudio.org/biography/william-s-burroughs-and-kurt-cobain-a-dossier/.

[35] "Noise Poetry: An Interview with Thurston Moore." Beatdom. August 08, 2016. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://www.beatdom.com/noise-poetry-an-interview-with-thurston-moore/.

[36] McCrary, Jim. "When Hunter S. Thompson Visited William S. Burroughs." WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS. May 21, 2014. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://www.williamsburroughs.org/features/category/guns.

[37] Knight, Brenda. Women of the Beat Generation: The Writers, Artists and Muses at the Heart of a Revolution. Berkeley, CA: Conari, 2010.

[38] Kerouac, Jack. On the Road. London: Penguin, 2000.

[39] Telephone interview by author. October 28, 2017.

[40] Grauerholz, James. ""The Death of Joan Vollmer: What Really Happened?"" Fifth Congress of the Americas, 2012. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://traumawien.at/stuff/theory/burroughs/deathofjoan-full.pdf.

[41] Black, Jack. You Can't Win. Nabat Books, 2001.

[42] In addition to Burroughs, musicians Sonny Rollins, Chet Baker, and Elvin Jones submitted too the heroin treatment program at Lexington.

[43] The CIA’s notorious MKUltra project was a sprawling covert research operation that, among other things, engaged in dosing Americans—often unwitting—with experimental mind altering substances. Among its goals was to “render the induction of hypnosis easier” and “enhance the ability of individuals to withstand privation, torture and coercion.” Eschner, Kat. "What We Know About the CIAs Midcentury Mind-Control Project." Smithsonian.com. April 13, 2017. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/what-we-know-about-cias-midcentury-mind-control-project-180962836/.

[44] Grauerholz, James. ""The Death of Joan Vollmer: What Really Happened?"" Fifth Congress of the Americas, 2012. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://traumawien.at/stuff/theory/burroughs/deathofjoan-full.pdf.

[45] Burroughs: The Movie. Directed by Howard Brookner. Performed by William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Lucien Carr, John Giorno. United Kingdom: Criterion, 1983. DVD.

[46] Grauerholz, James. ""The Death of Joan Vollmer: What Really Happened?"" Fifth Congress of the Americas, 2012. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://traumawien.at/stuff/theory/burroughs/deathofjoan-full.pdf.

[47] Burroughs, William S., and James Grauerholz. Last Words: The Final Journals of William S. Burroughs. New York: Grove Press, 2001.

[48] Stevens, Matthew Levi. Magical Universe of William S Burroughs. Place of Publication Not Identified: Mandrake Of Oxford, 2014.

[49] Bockris, Victor. "King of the Underground." Gadfly Online. August 1999. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://www.gadflyonline.com/home/archive/August99/archive-burroughs.html.

[50] "William S. Burroughs and Kurt Cobain — A Dossier." RealityStudio. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://realitystudio.org/biography/william-s-burroughs-and-kurt-cobain-a-dossier/.

[51] Telephone interview by author. October 28, 2017.

[52] "William S. Burroughs and Kurt Cobain — A Dossier." RealityStudio. Accessed April 12, 2018. http://realitystudio.org/biography/william-s-burroughs-and-kurt-cobain-a-dossier/.